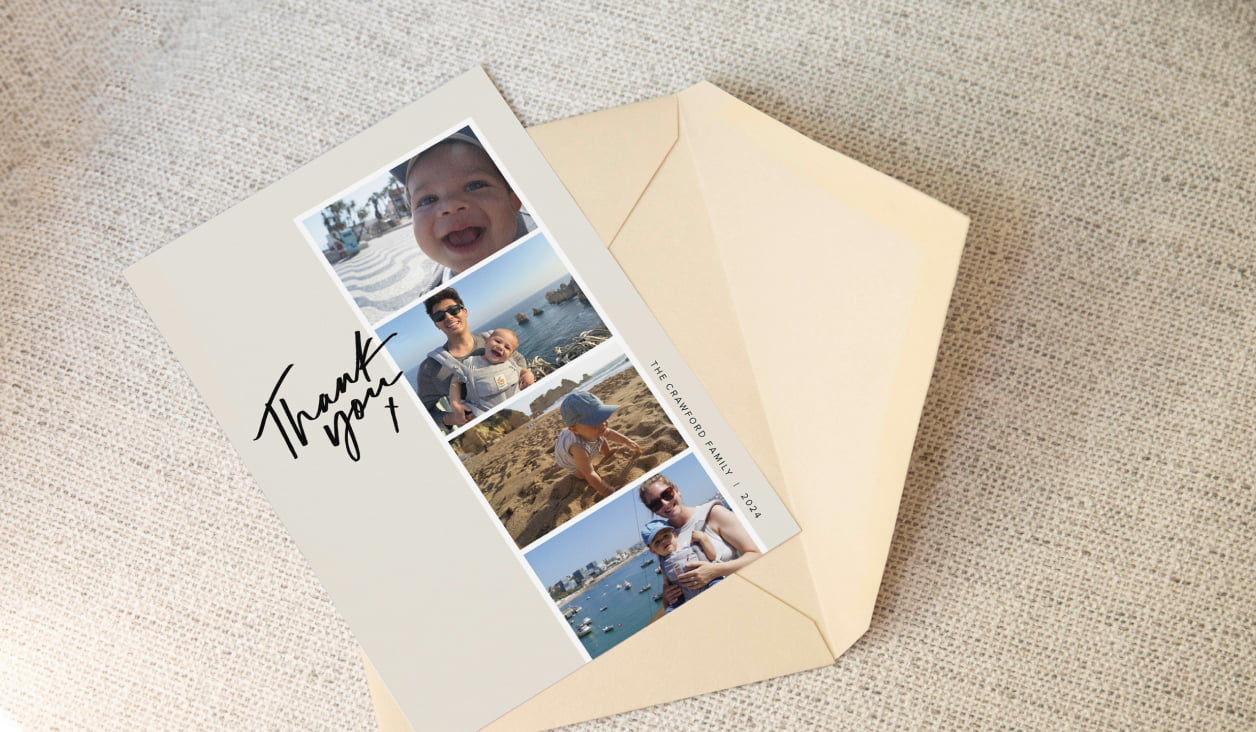

Think about all the photographs in your possession. Where are they stored? And more importantly, how? Your answer likely depends on your demographic cohort. If you're a Baby Boomer, you probably have boxes in the attic full of dime-store 3-by-5 prints in their original envelopes, strips of negatives in the little pocket in front. If you're a GenXer, perhaps you have beautifully embellished scrapbooks of snapshots from memorable family activities and milestones, plus every photo you've taken since you got your first iPhone stored (and ignored) on your desktop computer. If you're a Millennial, you probably have a whole Instagram feed of selfies and photos of what you ate for dinner.

It probably isn't a coincidence that scrapbooking as a hobby for home crafters really took off just as digital cameras did in the early 2000s. Once all our vacation snapshots were invisible to us—stored inside our point-and-shoots or on tiny little storage cards—we felt like somehow we were losing those memories. Inexpensive digital cameras made it easy for us to take lots of photos indiscriminately, but then we opted to print and save the best ones in keepsake books.

It also probably isn't a coincidence that vinyl records are enjoying newfound popularity among audiophiles who want a more authentic listening experience than what they get from iTunes.

While digital book sales continue to grow, that growth is slowing, and 80% of all books purchased are still in paperback or hardcover form. Even in this digital age, people still want the physical manifestations of those JPG, MP3 and PDF files. As it turns out, we may need them.

We take it on faith that our smartphones will always be able to display JPG images, that the "cloud" in which we've stored all our music and photos will always be there. But we're not guaranteed of that. Good luck finding a player for the mixtape your 8th-grade crush made you. Technology's only getting smaller, and while it will be possible to view your favorite pics on your smartwatch in the next few years, we can't imagine it being quite the same.

Managing and preserving all this digital media presents tremendous challenges, not just for libraries and educational institutions seeking to archive their collections for future generations, but for those of us who want to store our personal photos, videos and .doc files. "All of us have content that's vulnerable to destruction or loss, and we want to prevent that," says Mary Molinaro, director of the Research Data Center at the University of Kentucky Library and a leading educator with the Library of Congress's Digital Preservation Outreach and Education program.

"Content is vulnerable whenever you change computers or update software," she says. "When I present, I always ask people, how many of you have lost files? Everyone has.

People think digital media will always be there—but that's not necessarily the case," she continues. "I have boxes of family photos from the 1800s. But when my daughter's hard drive crashed, she lost all the baby pictures of her second child. People don't realize it until they lose things."

In a 2010 article for Harvard Magazine, Jonathan Shaw writes, "For digital preservationists, a prime concern is that data might be kept perfectly secure and complete, but still be unreadable by machines and programs in the future." Molinaro describes a recent move, when she discovered a box full of old zip disks—not only did she no longer have a zip drive, but even if she had, it would be incompatible with her current-model computer. (The disks went right in the trash.)

Then there's the issue of storing all this digital content. A study in 2013 by Backblaze, an online storage company, found that 22% of hard drives failed after four years, due to mechanical problems, random issues or overuse. In other words, we have to back up our backups. The irony is that digital media may be more ephemeral than print.

While files that were "born" digital are particularly challenging to organize, catalog and archive, objects that originated in print form can endure (presuming that they're archivally printed and stored). A cover of The New Yorker in 2009 illustrates the point: It showed a space alien sitting amid a pile of broken computer hardware and reading a book—the only thing that still "worked."

In an age when each of us has thousands of images, songs, e-books and documents, out of sight and out of mind on our desktops or in the cloud, we're entirely disconnected from all of it. But as creators and makers, we value things that make an impression, that are more permanent. We use technology as a means to produce our work, yet we prefer the physical product that results.

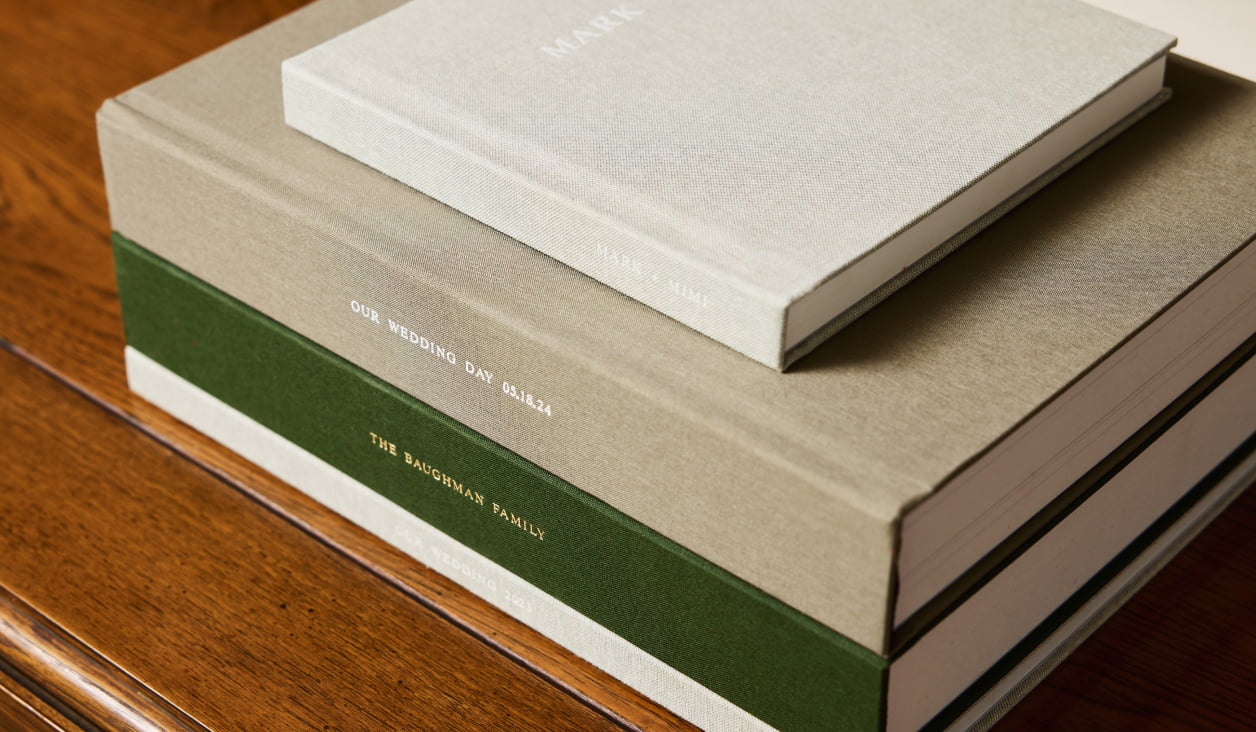

And when we expect those products to make an impression and to last, we have to plan for that permanence. Printed content must be made durable if it's to survive, so we have to make smart choices about form, production and materials.

We're in a time of transition — as we move from printed formats to digital media and back again, and use digital tools to create physical objects. Researchers and preservationists are in the same state of flux, Molinaro says. "In the library world, we digitize objects in our collection to make them more widely accessible, and we print them out for display. But the backup is still that printed object."

"Think of printed books," Molinaro says, in a nod to that New Yorker cover. "When you take a book off the shelf in 20 years, you can be pretty much guaranteed that the words will still be readable."

In a presentation to the American Association for the Advancement of Science, internet pioneer and Google's Chief Internet Evangelist, Vint Cerf, warned that the issue of digital data loss isn't just a problem in the here and now, but rather has sweeping historical consequences. We can't possibly know how valuable these materials will be decades or centuries from now: Family photos will be important to our descendants, and important research being done today will be vital to future scientists. We're facing a "forgotten generation or even a forgotten century," Cerf said.

"We digitize things because we think we will preserve them, but what we don't understand is that unless we take other steps, those digital versions may not be any better, and may even be worse, than the artifacts that we digitized," Cerf said in a 2015 article for The Guardian. "If there are photos you really care about, print them out."