It was a Tuesday Zoom call ripe with the nuance of life in 2020 — two teams separated by a novel pandemic, brought together in the face of historical divides. But as we "sat down" with the See In Black collective, societal uncertainties gave way to the simple promise of hope.

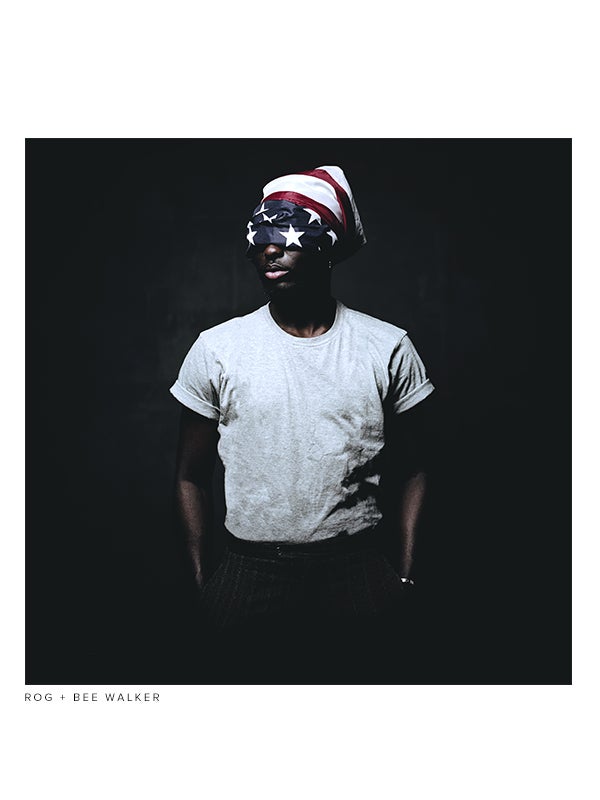

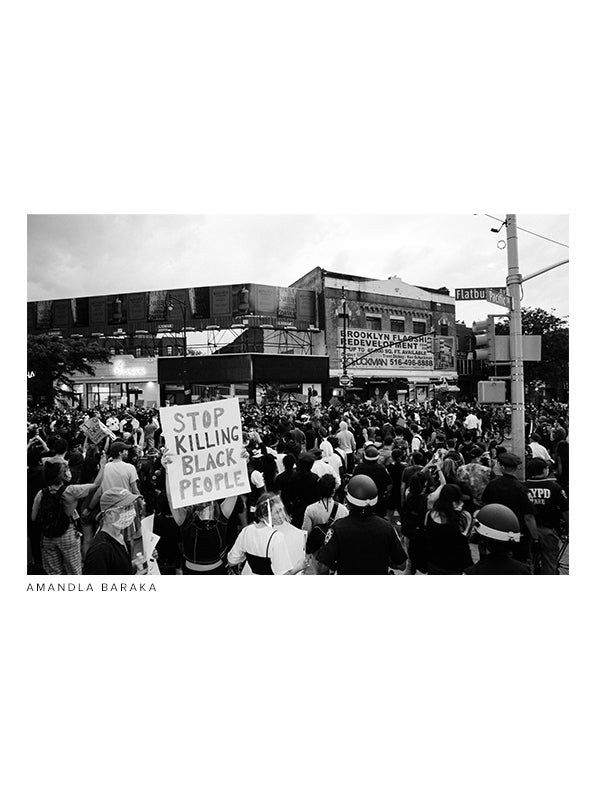

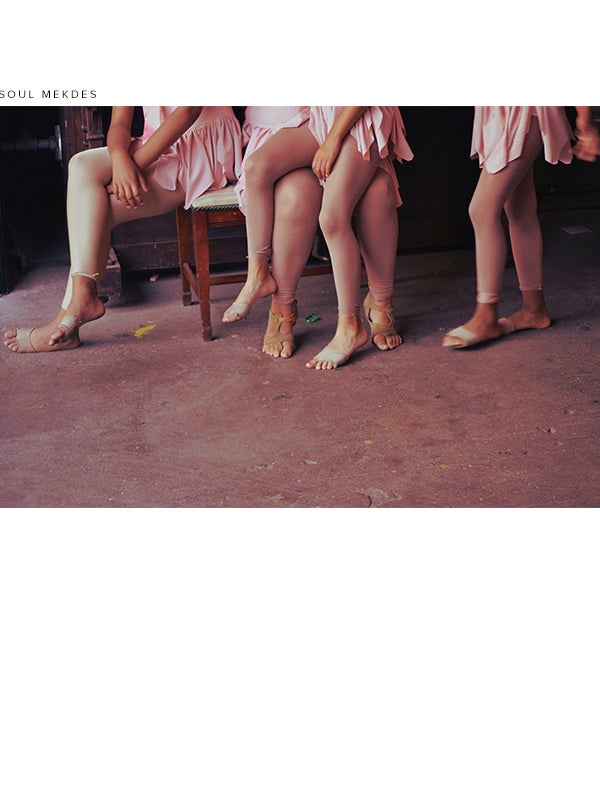

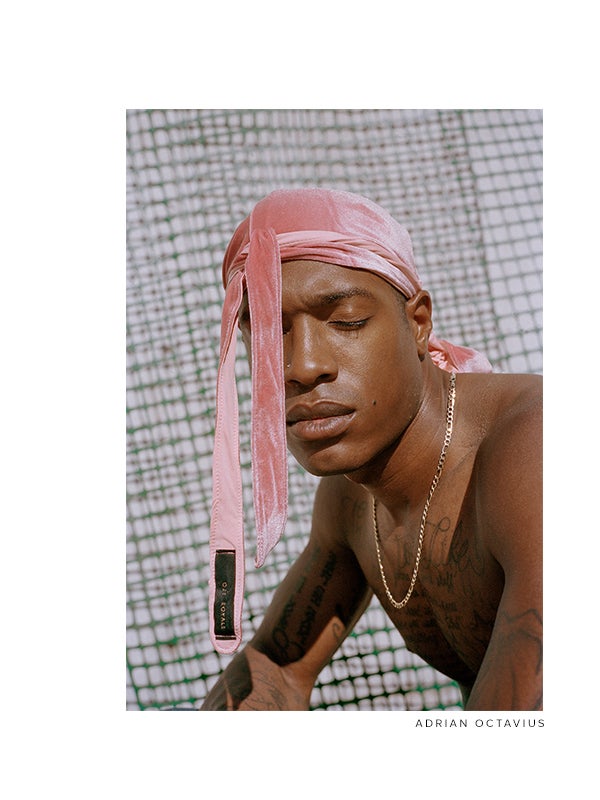

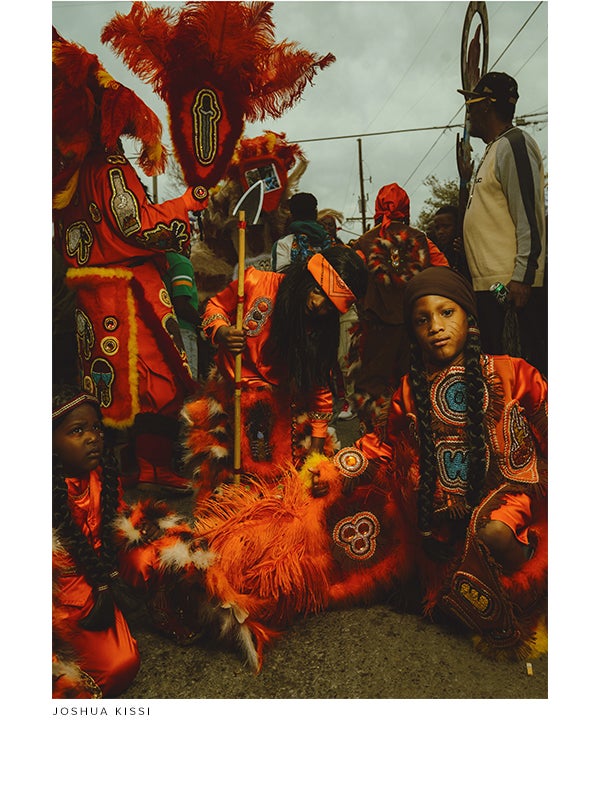

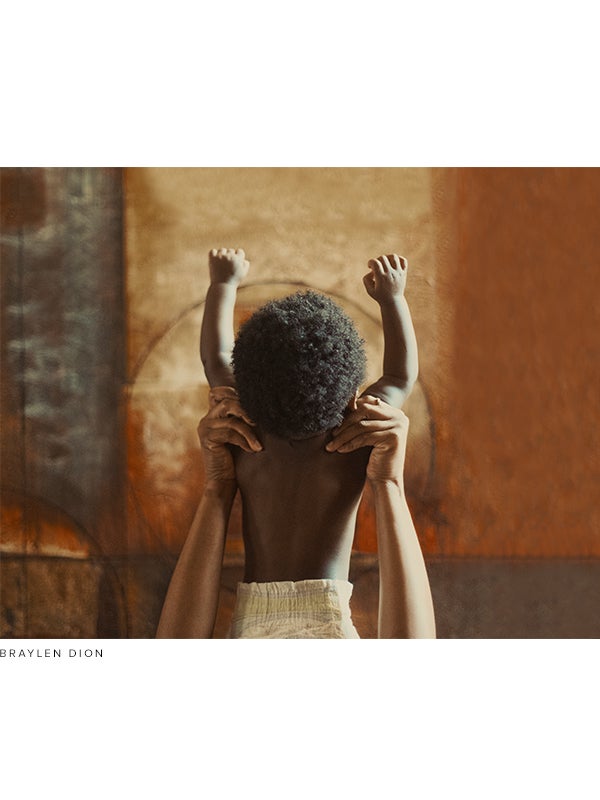

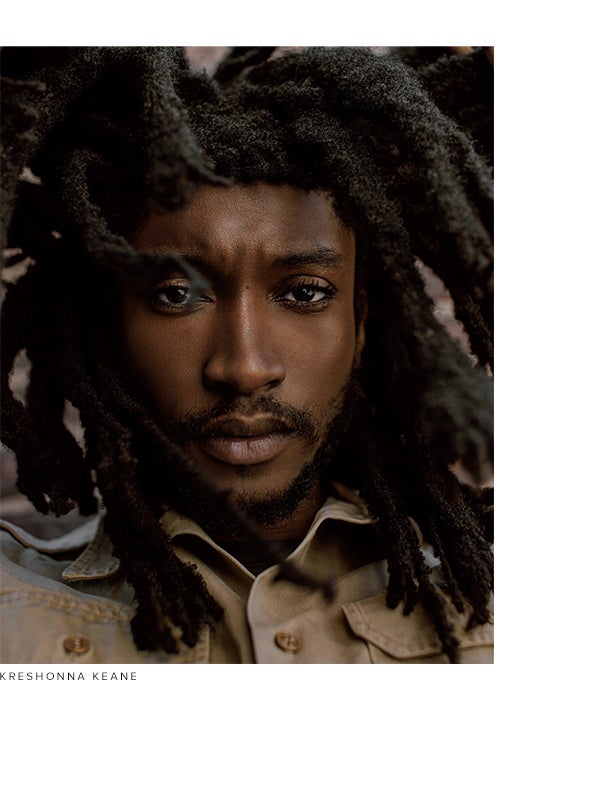

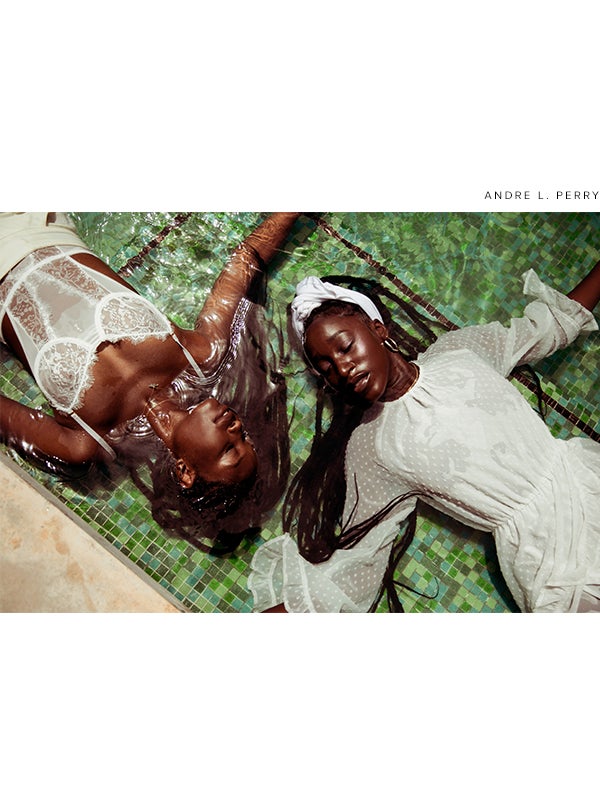

Organized by co-founders Joshua Kissi and Micaiah Carter, See In Black is a collective of Black photographers, formed in a call for the elevation of Black visibility. The group's first endeavor, launched on the Juneteenth holiday, is a powerful collection of prints from 80 Black photographers — curated under the umbrella of Black in America.

Every dollar of profits from prints sold will be directed to five nonprofits, each thoughtfully aligned to one of five pillars of Black prosperity: civil rights, education/arts, intersectionality, community building, and criminal justice reform.

We are grateful to play a small role in supporting this initiative, and we were just as honored to sit down with members for a discussion of mission and movement. In the words of See In Black members Joshua, Micaiah, Florian Koenigsberger, and Danielle Kwateng was a true reminder of the power and purpose of story — asserted through the unseen lens of what it is like to be Black in America.

More Than a Moment

Art, Archive, & What It Means to See in Black

There is power in amassing these voices and gathering them in a way that asserts we are to be counted...

How did the collective get started?

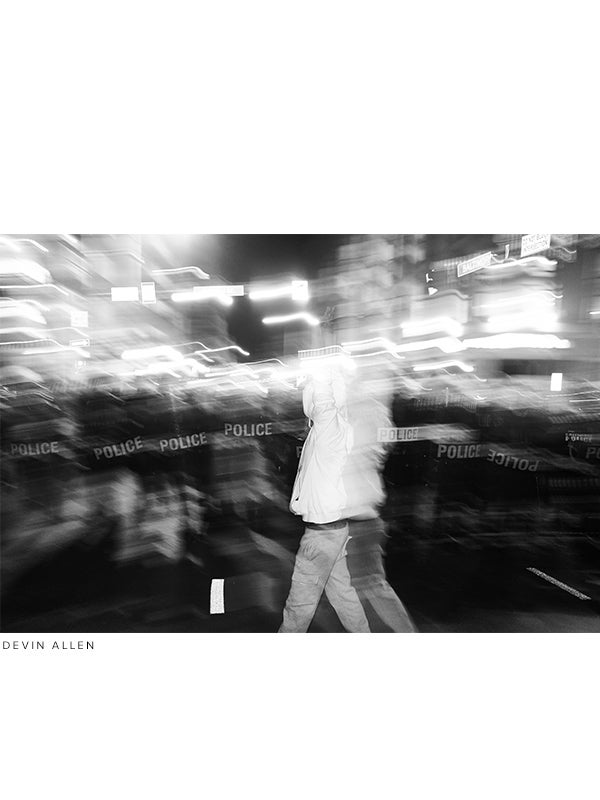

Joshua Kissi: I think with the climate that we're in now and the unfortunate death of George Floyd, you can't help but just feel helpless in a lot of ways. You want to respond as an artist, as a creative, as a photographer, but you also need to feel. As artists, or as photographers, it's important to feel first — because we're human before we even put a camera to our eye. Feel all the feelings you're supposed to, then from there, the next step will be apparent. Once the tragic death of George Floyd happened and even back to Ahmaud Arbery, it kind of reminded us from an intimate place why we do what we do.

Micaiah Carter: With Trayvon Martin and Eric Garner, when those things were happening, I was in school, and I think Joshua was in a different place too. Now we're in a space where we're able to connect with other photographers and people from the movement.

Joshua Kissi: Yeah. And I think, to even piggyback on Micaiah's point, throughout the past maybe 10 years, with the explosion of social and digital media and how obtainable photography has become, a lot of photographers who are Black have started to tell stories around their community.

Micaiah Carter: It's brought together a bigger scope of what Blackness is and opened doors in a lot of ways from just awareness. Especially with COVID being such a pandemic now, it's putting more attention on the movement, because people have more time to focus on other things. It's great to see everyone come together and show a vision of America — Black America that is.

Joshua Kissi:

For a long time, we just didn't have the liberty or privilege to be behind the camera as well. So telling those stories intimately with nuance and care is just something we hadn't seen as much as we have in the past 10 years of this Instagram explosion. We're always trying to find community within the Black photography network, but now more than ever, we saw the need to actually come together on a lot of things.

I think it's a bigger thing as well, because we have photographers who could sell their work for a lot more, and have sold their work for a lot more. In a lot of creative and art circles, it's hard to bring people together because of the different dynamics at play. But for over 70 Black photographers to be like, "Hey, this counts for me. It's an honor to be a part. Thank you for contacting me," it speaks volumes to what we can do together when we agree to say one or two statements that the world is ready to hear.

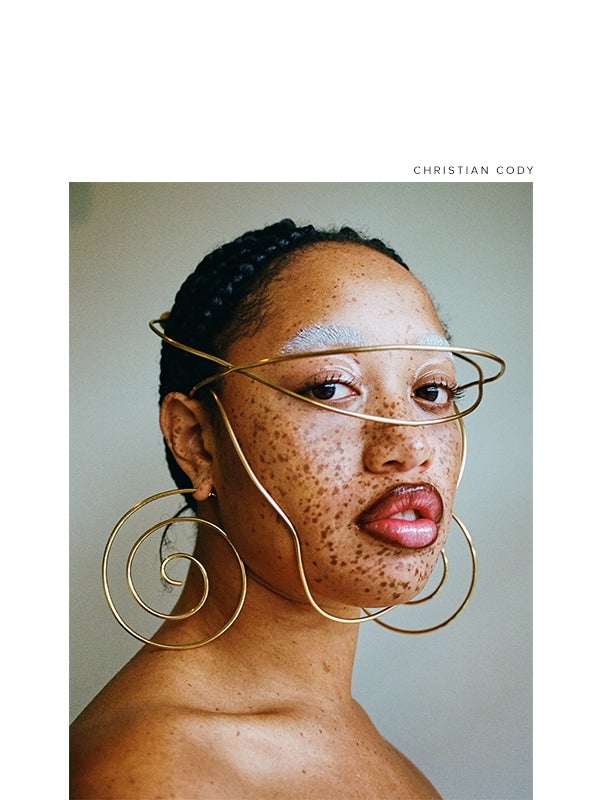

Images represent and challenge this idea of single narrative and, in their depth and breadth, give a multi-sidedness that has always been true for members of this community.

How is photography a tool that can help people tell their own stories?

Micaiah Carter: I feel like for me, for example, I'm really bad with writing and expressing myself with words. But with photography, I was able to evoke emotion without having to say anything. It's a way to express your life or express ways that you want to feel, because there's so many different layers — whether it's documenting versus kind of creating your own narrative in your own world.

Joshua Kissi:

Everything starts from an image, right? And I think images have an important historical context into how we see ourselves, but also how we see the rest of the world. So, even though there's, at this point, millions of images being photographed and taken, they work as a reference point.

And I think for right now, and especially within the past decade, it was important to kind of have our own page 'for us by us' because it's always been viewed through predominantly the white gaze. So to kind of separate that and be like, 'this is who we are' has been important, and I think will continue to be important.

We're showing that, not just for us, but also for the future generations. Like, you can do this, and it can be intimately about you, about your communities — and as nuanced and detailed as it gets, it becomes even more beautiful in that way.

Florian Koenigsberger:

I would add, if I could, the conversation about Black culture as a monolith, or specifically not being a monolith, is one that's been growing in mass culture — and images hold a unique power. Images represent and challenge this idea of single narrative and, in their depth and breadth, give a multi-sidedness that has always been true for members of this community to other people to take in as well.

It's been really exciting to see, as the image collection comes together, that so clearly reflected in the content that was shared. I think this also speaks to the curation — Joshua and Micaiah were very deliberate in the choice of photographers.

We really want to inspire people to do more, to feel more and just try to live their best lives — to have people pick up a tool and feel like they could actually change the world.

In the mission statement, you speak to the importance of being both artists and archivists. What lies at the intersection of the two?

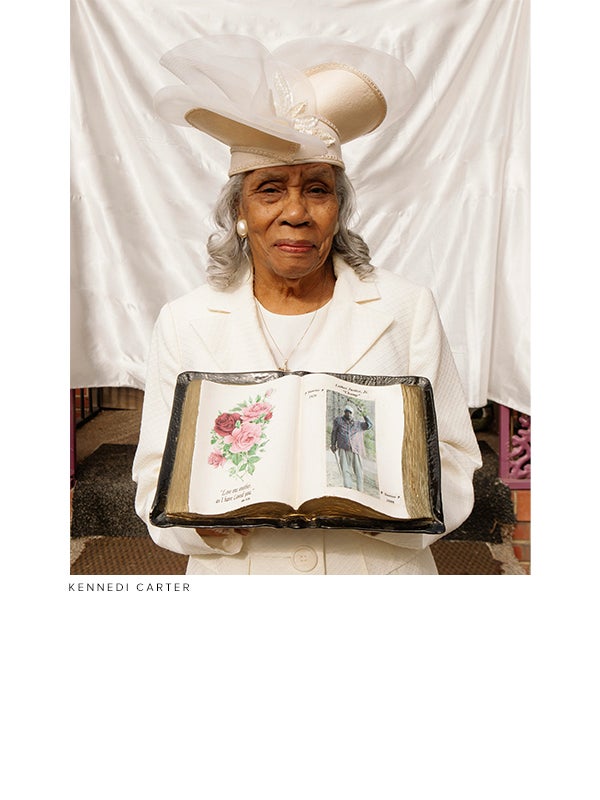

Micaiah Carter: I guess I can speak more from the artist's perspective. I've just started archiving my own family collection, which reconciles it to the work I do today. I think photography was super important ... just having a footprint of time. Backstory: My dad was from Kentucky, mom was from Oklahoma. My dad was drafted to the Vietnam war. And during that time, he was able to have a more stable economical status than my mother. So he was able to document a lot of that time. He has tons of scrapbooks like that. My mom doesn't have so much. That difference is what inspired my own work in creating languages and creating my own visions, but also having personal words beside the family portrait. Those moments mean so much in establishing a footprint in time.

Joshua Kissi:

I agree with that. The first form of photography I was introduced to was family photos. That inspired me. My parents came from Ghana, West Africa. There was a switch in their photography, in what I saw: A lot of their images had this sepia tone when they were in Ghana. It was really warm, the tones of the photos, what they were wearing. Then I see when they migrated to New York, a lot of jackets, a lot of colder tones, a different feeling. You've lived your whole adult life without this definition of racism. You come here and you're trying to balance that with raising your kids in a cultural way that's very Ghanaian or very West African.

For the most part, I was like, 'I want to be able to define more of that gray area,' and give a reference point to how you possibly could look at yourself, identity-wise, being Black in America, but also being within the diaspora of many different types of Black people from all over. When I think of 'archivist' and 'artist,' I think of those two things, and the connection between storytelling and truth-telling when it comes to your own story.

Florian Koenigsberger:

There's also a cultural, collective archive. A friend of mine said to me the other day that 2020 is probably going to be its own history book one day. We're dealing with so many crises of a scale overlapping at once that it feels like we haven't seen in our lifetimes.

I remember, when this friend said that to me, I thought back to the kinds of things I read in my history books. It was rare to hear about artists playing a role in the context of civil rights, especially in the United States' Civil Rights Movement, as history has been told en masse. I imagined a future in which we look at not just the pandemic as a public health crisis. Violence against the Black community is a public health crisis, shared as a burden by all of us.

There's power in the idea that a group of artists holds the tools to represent, dignify, and form a visual path to justice — powering organizations that have legal infrastructure and policy infrastructure to go implement some of those changes on behalf of this community. That idea of connecting the arts most directly to justice work in this way has a deep tradition, and is one that we're participating in the lineage of.

When I think of 'archivist' and 'artist,' I think of those two things, and the connection between storytelling and truth-telling when it comes to your own story.

What does it mean to make an image, and how is that different from documenting history?

Joshua Kissi:

I think even the language we use around photography can be really harmful, as far as the 'taking,' the 'documenting,' the 'shooting.' All of the language feeds into this imperial, colonialistic perception. Because, as important as it was to wage war on places, it was very important to also photograph what those places looked like, what those people looked like, to justify the means to explore and discover.

Every time I think about documenting, I have a love and hate relationship with the word. Because when I think of documenting, I immediately — because I'm born and raised in the West, and I'm born and raised here in America — think I own that narrative. I don't necessarily think that's true. There should be some work within the phonetics of photography language to undo that, because we know where it stems from.

What we're doing is sharing. If I'm sharing my perspective, sharing my story with yours, it becomes a more nuanced and diverse story. I look at myself as a truth teller and a storyteller, who has the opportunity and privilege to share other people's stories outside of myself — whether I'm deeply connected to them or just very much interested in them. I think, for a lot of artists, that's where it starts. Before, during, and after this, all we're going to have is stories. That's the most important part.

Florian Koenigsberger:

One of the things that I have been thinking about a lot in observing Joshua and Micaiah gather so many voices artistically is the assertion of what counts as history. As a group of photographers, I don't know if we are interpreted as part of the history at large or not. But, I do think that there is power in amassing those voices and gathering them in a way that asserts we are to be counted. We are to be paid attention to. We do belong in the same sentence as some of the other major institutions that have been playing in this space for a long time.

When we think about the conversation around artistic institutions right now, there is this perverse relationship between length of existence and validity. We know that there are underlying systemic reasons why some of these institutions have been able to survive and thrive as long as they have, and why there are not others like them in many communities, not just the Black community. I love this idea that history is being asserted in particular, versus trying to participate in a broader historical narrative.

What we're doing is sharing. If I'm sharing my perspective, sharing my story with yours, it becomes a more nuanced and diverse story. I look at myself as a truth teller and a storyteller, who has the opportunity and privilege to share other people's stories outside of myself...

How has being Black photographers shaped your perspectives and the lens through which you view the world?

Joshua Kissi:

I saw a tweet, and even though it was super sad, it was a reminder of what it really means to be Black in the world. It was like, 'Being Black means, before you're traveling to a country' — let's say you have the privilege of traveling — 'looking up that particular country and whether or not they have a strong racism presence or not.' That just shows the experience and normalized trauma.

Imagine having that experience in a myriad of ways, depending on who you are and what you identify as, then picking up a tool that gives you the ability to tell stories — not only your own stories, but other stories collectively.

As a Black photographer, I always felt like I had the due diligence to tell the truth — to put something that felt near and dear to my heart out there in the best way possible. If it impacts the next kid, I could go to sleep that night. I feel like I'm doing my job as long as it's impacting somebody in the world to feel more seen or to feel more heard. I feel like I'm doing exactly what I'm supposed to be doing as a Black photographer and a storyteller.

Micaiah Carter:

No, I think it's true, what you said, just to be seen. I think that's the biggest thing in all aspects for the Black community, especially in America. I think it's so diverse. Sometimes it can feel left out, even with bigger corporations thinking inclusion is a check mark. In terms of entertainment and colors, that affects girls growing up and boys growing up, not seeing themselves.

I think as Black photographers, it is telling the truth, and it's also expanding visions of it, and expanding other people's visions of what Blackness is. Not conceptualizing it for a consumer narrative, if that makes sense. Because at the end of the day, it's a human thing too. It's just a different experience — people have different, beautiful experiences that make everyone an individual.

At the end of the day, it's a human thing too. It's just a different experience — people have different, beautiful experiences that make everyone an individual.

Why did you choose these five organizations to donate to?

Micaiah Carter: I think we wanted to find organizations that did a plethora of things for specific communities, but also national communities — different intersections that need outreach, and need more eyes upon what they do and how people can help.

Joshua Kissi:

Yeah. Because, whether you like it or not, nonprofits have a certain view within creative communities, even, of what they do, how they do it, the branding, the storytelling aspect of it. If anything else, we just hope that there is a connection between what people are inspired by in the photos and what they aspire to see happen on the ground once they support these different nonprofits.

We really wanted to pinpoint nuance and intersectionality within the organizations we chose and just inspire people to think outside of themselves. An idea may start with you, but it shouldn't end with you.

Danielle Kwateng:

For the five charities we chose, we really spent a lot of time thinking about what Black prosperity looks like. I think there's a lot of discussion, especially right now with the current movement, about deliverables, action items, things that the Black community needs now to address the systemic racism that this country was literally founded on. I think for us, it felt like, let's break it out into five different pillars of things that can be directly addressed.

There are a lot of great campaigns that maybe go to one organization or work with one group. But we felt in order to truly herald Black prosperity, we can't just think about one section or one piece of the pie. It's really a cohesive movement. There are different aspects to making life better for Black people.

Beyond raising money for five meaningful causes, what do you hope will come out of the creation and continuation of this collective and others like it?

Joshua Kissi:

More reference points, more possibilities. The plan is to continue to do things like this, community-facing aspects, and really build out this collective and coalition to exist beyond peak trauma moments like now. Which is important, but at the same time we definitely want to have a sustained plan on how we impact communities on the ground, how we galvanize together.

We want this to really, truly impact lives and hopefully inspire more collectives and groups to get as nuanced as possible. There should be a Black trans photography collective. All these things should exist — or if we could house it in our collective and just have different tiers of it, that's also beautiful. But I think more than anything else, we really want to inspire people to do more, to feel more and just try to live their best lives — to have people pick up a tool and feel like they could actually change the world. It sounds corny, but I think that's what we try to do every day in the work that we create.

So July 3rd, I'm really looking forward to, more than anything, just saying we did it. We actually came up with an idea and executed it. Where it falls in that scale is really not up to us to judge, but just the fact that we did it is a success.

I look at myself as a truth teller and a storyteller, who has the opportunity and privilege to share other people's stories... Before, during, and after this, all we're going to have is stories. That's the most important part.

Micaiah Carter: And to add to that, I feel like the biggest thing is having everyone come together under this umbrella. I've never really seen something like this before where the future can extend to not just to the people on the list, but to people that are in high school and people that really want their own viewpoint for their inspirations and a way to connect to that — which I think would be great.

Florian Koenigsberger:

I don't think we spoke directly about moment versus movement. I work full-time as a product marketer at Google, and I'm also a photographer. And there's a lot of pressure, especially for folks in a corporate context right now who are Black, to figure out how to capitalize on this moment at work to make change happen. And I've often been asked if I think it's f****d up, that it took this level of a crisis to finally have attention paid to some of those things. And my answer has been, of course it is. But what's more f****d up is the frantic energy with which so many Black employees are pursuing this moment because they believe that it's not going to exist in two weeks.

By taking these objects and putting them into homes and on walls that people look at and engage with on a daily basis, it is also an assertion that the value of this community and our needs and our voice has longevity beyond whatever the news-headline cycle is going to be. And I think that, especially in a culture that is moving away from viewing image prints and is increasingly obsessed with screens that allow us to wipe memory pretty quickly — literally in a scrolling motion — this idea of creating permanence via prints is something that's really resonated with me as part of the mission to put work in people's hands.

Joshua Kissi: That's an anchor, man. That's how you anchor an interview.

By taking these objects and putting them into homes and on walls that people look at and engage with on a daily basis, it is also an assertion that the value of this community and our needs and our voice has longevity beyond whatever the news-headline cycle is going to be.